- September 12, 2025

by JP Pawliw, September 4, 2025, Updated September 5, 2025

Every two years, like clockwork, one of the largest automotive parts manufacturers in the world faced what it called a “big event”: a large project went off the rails, costing the company a minimum of $80 million to $100 million each time. When a new president joined the organization, he decided to investigate what was behind this expensive pattern.

The problem, he discovered, was that people in the organization were not willing to risk giving feedback up the org chart until it was too late—once a situation escalated, and they had no choice but to go outside the plant and ask headquarters for help. As in many companies, a phenomenon called “CEO disease” prevailed: the higher up leaders go in an organization, the less candid feedback and information they get from below.

This is just one example of how employees’ failure to take risks (in this case, the risk of speaking up) can have outsized consequences for teams and organizations. In reality, people need to go out on a limb in order to achieve high performance. Unless they are willing to name an inconvenient truth about a strategy or product, make a difficult decision, or raise their voice about an issue, it’s difficult for companies to go beyond what has been done before and to build something differentiated from competitors’ offerings.

And yet risk-taking goes against the operating model of human beings—their biology—which defaults to protection, especially when feeling pressure to perform. Taking any risk triggers a clash between the requirements of high performance and how our brains try to protect us. I call this clash the fundamental conflict of performance: at the exact time an organization needs people to take risks to move fast to execute the strategy, their brains are defaulting to protection.

So, how can companies address this clash and get employees to take risks more often?

My experience working with coaches of high-performing teams in the NFL, NBA, and Olympics—combined with research from my organization, the Institute for Health and Human Potential—has helped us identify strategies that enable teams to take more risks and improve faster than their competitors. And it all starts with a number: 8%.

The Last 8%

In a multiyear survey of 34,000 people that looked at a range of risks—from making hard decisions, to naming inconvenient truths, to having the hardest parts of a conversation—my organization found that there is a gap between the risk people feel they should take in a situation and the actual risk they do take.

In conversations, for example, people tend to leave out an average 7.56%—rounded up to 8%—of what they want to say. They are comfortable enough discussing the first 92%, but when they get to the more challenging parts—those that have the biggest consequences for the other person or the project—they get caught up in how their counterpart is reacting, or is perceived to be reacting, and they avoid having the full conversation.

It is the same with hard decisions. Most people are comfortable making the easier choices they face, but when there’s a risk involved in making a decision—one they perceive will upset others, such as who gets promoted and what projects should get supported—they back off, procrastinate, and struggle to take action.

We’ve named this gap the last 8%.

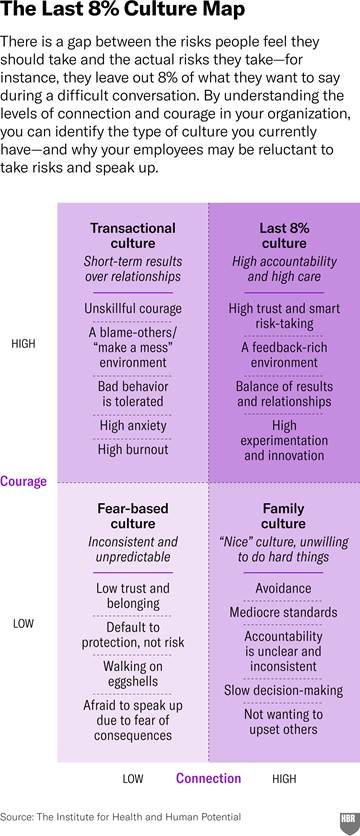

Our work also identified the kind of team culture and environment that enables people to more frequently take risks—to close the 8%—and the three kinds of team cultures that do the opposite, acting as barriers to taking risks. Those insights came from a study we conducted of over 72,000 people in which we asked individuals to describe the elements of their team they perceived to be barriers to, and enablers of, taking risks to do hard things.

The data shows that enabling high performance through smart risk-taking has two pillars: high connection, meaning people perceive they have a voice, are valued, and feel psychological safety; and high courage, meaning people are capable of, encouraged to, and enabled by norms to be courageous to execute on hard things, such as holding people accountable. When high connection and high courage are both in place, a culture of trust is built that enables people to take more risks—in other words, a last 8% culture.

Of course, not all teams in organizations have both high connection and high courage. For 67% of our respondents, one or both of the pillars were perceived to be at levels that were insufficient to drive performance. In these instances, we saw teams default to one of three culture types that impair risk-taking and performance: family, transactional, or fear-based. These patterns occur independent of industry and company size.

Let’s look at each culture in turn.

See more HBR charts in Data & Visuals

Family Culture: High Connection, Low Courage

When a culture has high connection but low courage, we call it a family culture. It exists in the lower right-hand quadrant of the map and is characterized by being “nice” but unwilling or unable to do difficult things. We found that 37% of the people in our survey, the largest cluster, belong to teams with a family culture.

In this environment, people sugarcoat communication. Taking cues from and modeling their behavior on that of their manager, people on these teams don’t make tough decisions or name inconvenient truths. Why? Groupthink is in effect; employees don’t speak up because they don’t want to upset others. It is, at heart, an avoidance strategy driven by people not wanting to experience (or not having the capability to manage) difficult emotions. A family culture might be high on care, but a lack of sufficient accountability breeds mediocre standards; in addition, decision-making is slow because people try to include everyone in the process.

Transactional Culture: Low Connection, High Courage

A transactional culture, which makes up 14% of our sample, sits in the opposite corner of the map and features low connection and high courage. It is characterized by prioritizing short-term results over both relationships and the culture of the team.

In these environments, there is less avoidance than in a family culture. It’s more common for people to attempt hard things, which does take courage—but that courage is unskillful or even cutthroat. Managers, for example, do not hold back on pointing out inconvenient truths or giving feedback, but because of a lack of skill and connection with others, a lack of interest in how their delivery affects employees, or because their focus is on short-term results, they can be perceived as harsh and unyielding. In our terminology, they “make a mess.” That sets the tone for everyone and gets in the way of the team being able to explore disagreements or talk through tensions together. These managers often hold a belief that the only way to get results is by pushing their people to do more, creating impossible targets and unreasonable timelines (often driven by pressure they feel from above).

In a transactional culture, short-term results can be achieved, but they are generally not sustainable because, over time, team members feel less of a sense of belonging and an emotional commitment. They start to check out, burn out, stop giving discretionary effort, and are less open to putting themselves on the line to take risks. They also, relatedly, have an increased intention to leave.

Fear-Based Culture: Low Connection, Low Courage

There is a third culture type that acts as a barrier to people taking risks to do hard things: fear-based. In this culture, which made up 16% of our sample, teams have both low connection and low courage.

This type of team culture can feel similar to a transactional culture, but it is characterized by inconsistency and unpredictability. At least in a transactional culture, people know how their manager is going to show up. In fear-based cultures managers are all over the place: sometimes they provide feedback and are open to listening to team members, but other times they offer no feedback and do not listen. This lack of consistency creates great anxiety and causes people to feel like they are walking on eggshells. They stop taking risks, such as speaking up when they see something wrong or when they have an idea that could help, for fear of personal judgment. The groupthink that happens is less about not wanting to upset others, as in a family culture, and more about self-preservation. People don’t want to put themselves in harm’s way.

One common trait of fear-based cultures is that people often have to endure toxic “bad apples,” those team members who display negativity, withhold effort, or violate important interpersonal norms. When just one of these people is on a team, it has a spillover effect, causing other team members to take on the same behaviors: they argue and fight more, do not share relevant information, and communicate less. Why do teams with this culture type endure toxic bad apples? Because short-term results matter more than anything else.

Last 8% Culture: High Connection, High Courage

There is an alternative to the first three cultures—a culture where people step in and take risks to do hard things, with both high courage and high connection. This last 8% culture made up 33% of our sample.

In this culture, people feel connected, a sense of belonging and trust, and are enabled through team norms to be courageous. The dominant behavioral characteristics, modeled by their manager, are high accountability and high care. People know where they stand with their manager and colleagues because messages are not sugarcoated. Instead, the environment is feedback-rich, which creates a level of trust that enables people to take smart risks. Importantly, feedback and accountability are delivered with high care, helping employees feel genuinely valued and listened to even if they are not agreed with. They still feel they belong even when there is discomfort and tensions rise. That in turn means they are more able to hear and make use of criticism. They know that their manager is looking out for them and, crucially, understand the intention behind the feedback and accountability: the pursuit of a clear, big goal.

Last 8% cultures have a drive for results—but not at the expense of relationships. It is through strong relationships that people collaborate to achieve these results. Importantly, high care is also about people caring deeply about the work. There is purpose and pride in what they do and who they do it with. Subsequently, they are more emotionally committed, give extra effort, and attempt hard things because it matters to them and the team. These cultures have all the elements to help people take the kind of interpersonal and strategic risks that lead to real innovation.

Building a High Performance Team: Where Are You on the Map?

The first step in achieving a Last 8% Culture is understanding where your team currently stands. You can start assessing your culture and norms by reflecting on which of the map’s quadrants feels most like how things get done on your team. Ask yourself the questions below, drawn from the assessment we use with clients—and be honest with your answers, even if they’re uncomfortable.

- Do people feel connected to each other, but avoid doing hard things such as naming inconvenient truths and having tough conversations? (The Family quadrant.)

- Do people do hard things, such as naming inconvenient truths and having tough conversations, but not feel as connected to each other as you or they would like? (The Transactional quadrant.)

- Do people avoid doing hard things and also feel disconnected from each other? (The Fear-Based quadrant.)

- Do people skillfully do hard things and also engage in the difficult work to discuss issues the team faces? (The Last 8% quadrant.)

While it matters what you think, it matters just as much—or more—what your team thinks. At your next meeting, start a conversation about which quadrant employees think the team is in. To help you have the discussion, below is an outline you can follow, based on the protocol we use with clients.

- Tell employees that you’d like to have an honest conversation about your team’s culture.

- Show the culture map and describe each quadrant.

- If honestly and frankness aren’t the norm on your team, it makes a big difference to be vulnerable about why the team’s culture matters to you. Consider sharing stories about previous teams you’ve worked on where the culture either was or wasn’t good, and why that was meaningful for you. If you don’t think you are in the upper right-hand quadrant—a last 8% culture—share where you think the team is at now, why, and how you might be part of the reason.

- Ask employees where they think the team is on the map. Which quadrant feels most familiar, and why?

- Ask what the team can do to move closer to a last 8% culture. Offer your ideas first about your contribution—what you need to do to get to the culture you want, and invite people to offer other ideas.

- Depending on how the conversation has gone so far, ask what commitments the group can make as a result of the discussion. We suggest making three. These commitments are crucial to make before facing last 8% situations because they will carry employees through hard moments when it is easier to avoid taking risks.

No matter how the discussion goes, do not get defensive. This is an opportunity to influence the culture just by how you show up: Do you give employees a voice? Value their opinions? Make them feel safe, even if you disagree with them? What you do signals to others which behaviors are acceptable and rewarded—and they’ll remember it. Our clients find these conversations, when done right, to be some of the richest they have as a team, giving them a concrete way to move the needle on their culture.

Finally, make a personal commitment to own your team’s culture. Because culture exists more at the team level than at the organizational level, you, not the CEO or CHRO, need to take charge of the norms you want to have. When employees see you being vulnerable about what you can do to improve things, and see that you are genuinely open to what they have to say, they will feel less threatened, and the probability will go up that they will feel safer to take more risks themselves. This is how you build a high-performing team.

Your team members have the ability to be courageous to do hard things. But they face a fundamental clash between the requirements of high performance and how their brains try to protect them. Your job is to create the conditions—the culture—so they can perform at their best and achieve results that matter.

To view the orginial posting, please follow this link to Harvard Business Review’s website: The Secret to Building a High-Performing Team